Those Were The Days: The legend who laid the blueprint to map India from St. Thomas Mount

The East India Company’s initial response to Lambton’s proposal was lukewarm, and there was mockery at the Fort prior to financing it. With a myopic vision of the future, a member of the finance committee would remark, “If any traveller wishes to travel to Srirangapatna, he needs to only instruct his palanquin bearer. Why would we need to refer to Lambton’s map?”;

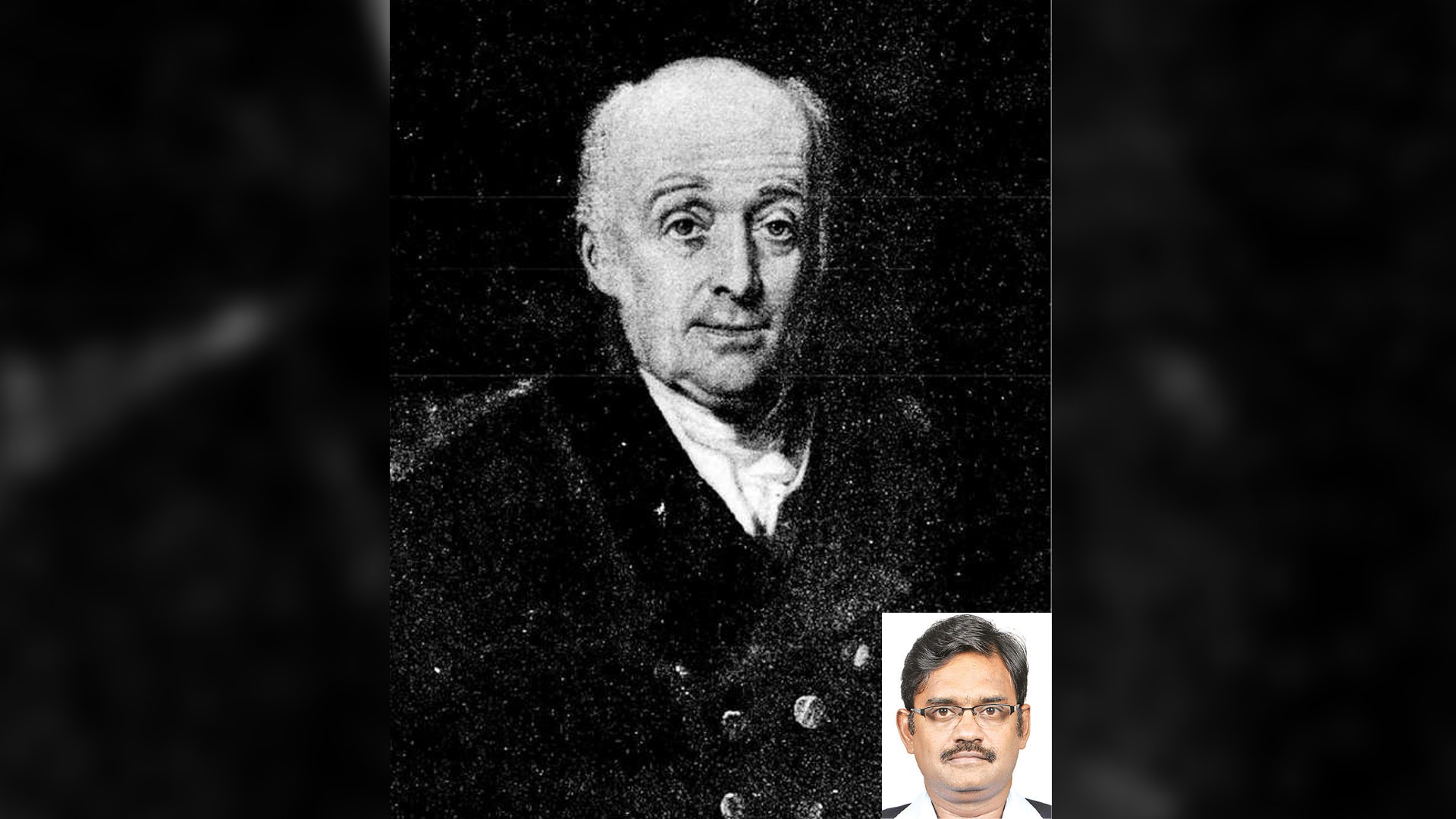

Chennai: IT might have been considered unthinkable to install a statue in honour of a British soldier of the much-reviled East India company in a prominent location of Madras after India gained its independence. But yet, there was one such instance when a statue for Lieutenant-Colonel William Lambton (circa 1753-1823) was erected at St Thomas Mount in 2003. Lambton was the Lieutenant Colonel, who embarked upon a large-scale trigonometrical survey across the width of the peninsula of India between Madras and Mangalore, and then continued his survey northwards for over 20 years, on a mission to map the entirety of British India.

Lambton’s story can be traced back to that point of time in India’s history when the East India Company transitioned from having merely commercial interests in the subcontinent to actually establishing a foothold for the British empire here. As they decided to run the country like a corporation, they were keen on knowing how much territory of India they really controlled and wanted to scientifically and precisely measure the expanse of their footprint. For this purpose, they commissioned three surveys simultaneously. One of them was an agricultural survey, a topographical survey and of course, the scientific endeavour that came to be known as the Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS) of India of 1802, that was spearheaded by Lambton.

It was after the defeat of Tipu Sultan, the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore at the hands of the East India Company during the siege of Srirangapatna, that the Company could embark on free movement throughout the subcontinent. And as a technology, the triangulation method had been perfected to measure land. So one may ask, why choose Madras as a starting point? For starters, Madras already had a School of Survey that was set up for Anglo Indian orphans near Fort St George in Poonamallee High Road (The Fort St George School of Survey was rechristened as the College of Engineering, Guindy later).

Lambton came from a family of limited means, and as a young military man, he fought and was taken prisoner in the American War of Independence. His inquisitive bent of mind once led him to foolishly look through a telescope at a solar eclipse without the necessary filters, which burnt the retina of his left eye. But he continued to serve in the British Army, this time under Duke Wellington, a soldier who had conquered two of the greatest generals the world had known in that era. Lambton would participate in the defeat of the first – Tipu sultan. He proved his military and scientific acumen during the Siege of Srirangapatna. His skills of navigation guided by the stars during the campaign had prevented a critical error during a night time manoeuvre, which could have otherwise changed the tide of battle dramatically.

After the success of the Mysore War, Lambton’s regiment returned to England and many of his colleagues fought Napoleon. But his dedication to the science of surveying compelled Lambton to stay back. He had proposed to the Company to conduct a mathematical and geographical survey of India that would cover the whole subcontinent with a network of triangulation. His proposal involved using the Callde triangulation, a trigonometric formula that calculated the distance between three mutually visible reference points (triangulation often uses quadrilaterals and occasionally polygons). Lambton declared that when he would be through with his job, he would have charted a meridian arc right up the centre of India – from the southern tip of Kanyakumari to as far as the Himalayas.

The East India Company’s initial response to Lambton’s proposal was lukewarm, and there was mockery at the Fort prior to financing it. With a myopic vision of the future, a member of the finance committee would remark, “If any traveller wishes to travel to Srirangapatna, he needs to only instruct his palanquin bearer. Why would we need to refer to Lambton’s map?”

But Lambton’s chief Sir Arthur Wellesley put pressure on the Governor of Madras to support Lambton. When an expensive theodolite (surveying equipment) was refused by the Company, he managed to procure alternatives, and borrowed barometers, while building his own hygrometers. Lambton’s enthusiasm was infectious and the conservative Company soon turned into a willing collaborator as the work proceeded. Mule carts and pack bulls by the hundreds, even elephants and a thousand men were at Lambton’s beck and call.

Over 40,000 individuals would be part of this survey that had overrun all possible deadlines. The Company had estimated that this project would take just about five years, but it took about 70 years, well past its own lifespan as the Company went defunct in 1857. It was the largest manual land survey expedition undertaken in the world’s history.

The first step towards mapping India started with a plan to compute the distance from Madras to Mangalore. The first measurement started from St Thomas Mount and the seven mile baseline extended from there to a hill at Perumbakkam near Tambaram. Precision was maintained and few values can be contested even today. The exactitude led to a great geographical discovery as well. Lambton’s survey measured the meridian arc near the Equator and his measurement was used to derive the ellipsoid of the earth. The earth was not a perfect globe, but more like an orange.

His survey team, which perpetually needed spots that offered a higher vantage point, used hills wherever possible. On the plains of the Cauvery Delta, the team used bamboo platforms and masonry towers as the base. While surveying Tanjore district, Lambton is said to have mentioned that the country was so flat that he had difficulty in locating any natural elevation for sighting. He therefore employed the gopurams of temples that dotted almost every village and completed the land survey.

On one occasion, a giant theodolite used by Lambton, fell from the top of the 216-foot tall Tanjore Big Temple and was badly damaged. He had to spend months repairing it under a tent pitched in open country, before he could restart his work. It is still debated whether he was compelled to stay put by the locals until the vimana (the structure over the inner sanctum in temples) was repaired.

The theodolite, which weighed half a ton, had damaged sculptures on the temple’s facade. Interestingly, among the replacement figurines that were placed on the facade, there seems to be a pointer to European presence, and this particular accident in the temple, thanks to the work of an unnamed, but nevertheless witty artisan. Among the ethnic figurines, there is also a sculpture of a man in a hat bears an eerie resemblance to Lambton.

In 1823, after charting out the bulk of south India, Lambton is said to have breathed his last near Wardha, his dream to map India remaining unfulfilled. But the Great Indian Arc of the Meridian, that his survey mapped out on foot, is considered a paramount scientific achievement of the 19th century.

So are there any traces of this survey that remain today? An arrow-like notation found on a short structure on the terrace of the St Thomas Mount Church would perhaps indicate the place from where the first plumb line was dropped for the Great Trigonometrical Survey. The country is dotted with many such GTS stations. A station consists of a square or rectangular-shaped platform with a pillar on top of it with an etched circle inscribed with a dot. While those at St Thomas Mount and at the Meteorological Station in Nungambakkam survive, those at Injambakkam and Red Hills have vanished.

Long after he died, Lambton’s survey would eventually establish that in the Himalayas, Peak XV, which then had no known local name, had the highest altitude above mean sea level in the world. And it was not Lambton, but his successor, who headed the survey team, after whom the peak would be named – Sir George Everest.

— The writer is a historian and an author

Visit news.dtnext.in to explore our interactive epaper!

Download the DT Next app for more exciting features!

Click here for iOS

Click here for Android