Ruin hunters: What lies beneath the Vatican of the Zapotecs?

Spanish chroniclers christened Mitla the Vatican of the Zapotec religion, and its wonders were said to continue underground;

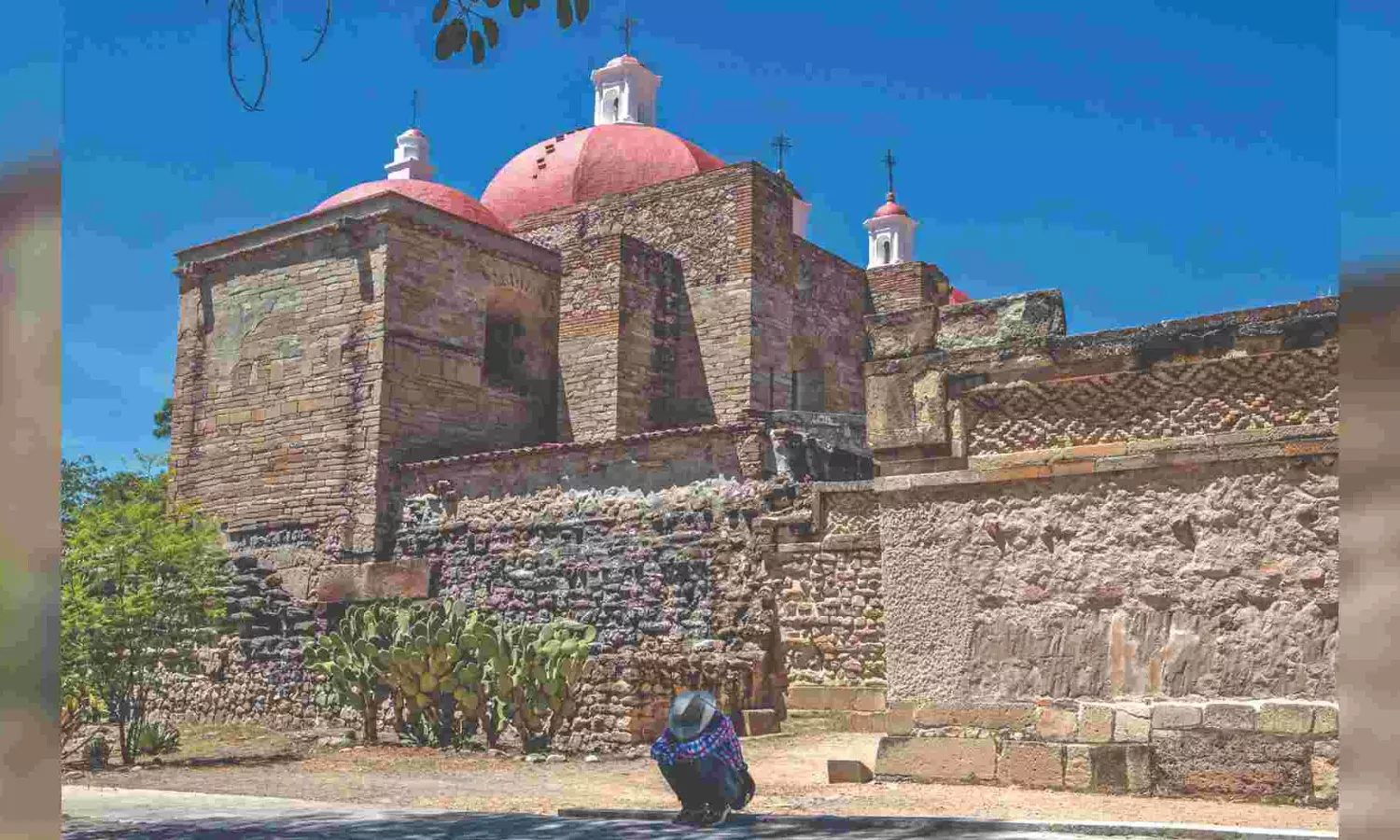

Representative Image

The ruins of Mitla sit about 30 miles from Oaxaca in the mountains of southern Mexico, built on a high valley floor as a gateway between the world of the living and the dead. The site was established in roughly 200 A.D. as a fortified village, and then as a burial ground by the Zapotecs, the so-called Cloud People, who settled in the region around 1,500 B.C.

Five main sets of ruins are scattered throughout the small modern tourist hub that is San Pablo Villa de Mitla. Some are royal houses and ceremonial centers featuring central plazas. One is a crumbling pyramid, and another is a domed Spanish church with adjoining Zapotec courtyards. Elaborate mosaics cover the walls, meandering geometric friezes resembling carved lace; “petrified weaving” is how Aldous Huxley described them in his 1934 travelogue, “Beyond the Mexique Bay.” Traces of color linger on masonry that was once slathered in bright red paint made by grinding cochinillas, wood lice that live on nopal cactuses.

Spanish chroniclers christened Mitla the Vatican of the Zapotec religion, and its wonders were said to continue underground. The Zapotecs, known for their metaphysical connection to rain, thunder and lightning, believed that they could commune with gods and ancestral spirits in an earthen cavity below their city, which led to a netherworld known as Lyobaa, the “place of rest.”

In 1674, Francisco de Burgoa, a Dominican friar, wrote an account, based largely on church documents, of Spanish missionaries who had explored a sprawling labyrinth of tunnels and burial chambers beneath the ruins of a monumental palace. A century earlier, secular clergy had blocked the doorways to the sunken complex with bricks and mortar, presumably either to keep the masses out or the ghosts in.

“The Spanish believed that demons performed black magic in the underground tombs,” said Denisse Argote, a researcher at the National Institute of History and Anthropology in Mexico. In September, Dr. Argote and a team of 13 geophysicists, engineers and archaeologists spent a week at Mitla for the second season of an ambitious exploration to determine what remains of the Zapotecs’ long-abandoned catacombs. In the still, steady calm of morning, they lugged around enough electronic ganglia to jump-start the Bride of Frankenstein.

Hard by the courtyards was the Church of San Pablo, a Catholic house of worship. The church was built in 1590, seven decades after Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Oaxaca Valley. Members of the Dominican order assembled it atop the sacred ruins, re-purposing stones from the palace. By severing the Zapotecs from their pagan deities, the missionaries hoped to convert them to Christianity. “Instead of trying to kill off the Zapotecs’ religious beliefs,” Dr. Argote said, “it was easier just to wash their brains with new beliefs.”