Scientists debut lab models of human embryos

“We know the basics, but the very fine details we just don’t know,” said Jacob Hanna, a developmental biologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

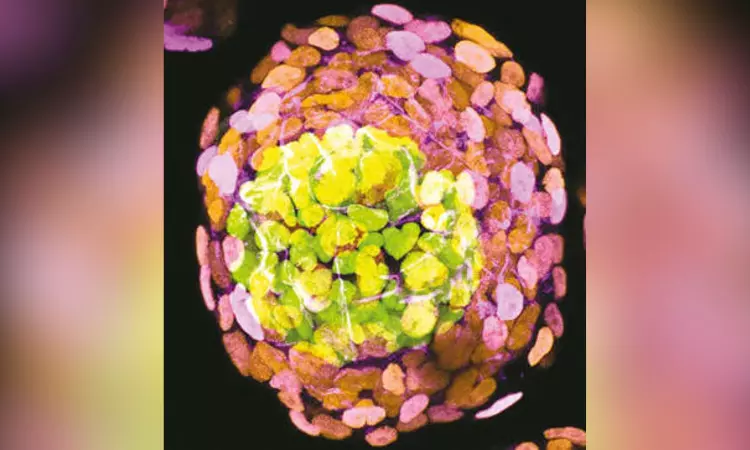

CHENNAI: In its first week, a fertilized human egg develops into a hollow ball of 200 cells and then implants itself on the wall of the uterus. Over the next three weeks, it divides into the distinct tissues of a human body. And those crucial few weeks remain, for the most part, a black box.

“We know the basics, but the very fine details we just don’t know,” said Jacob Hanna, a developmental biologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

Dr. Hanna and a number of other biologists are trying to uncover those details by creating models of human embryos in the lab. They are coaxing stem cells to organize themselves into clumps that take on some of the crucial hallmarks of real embryos.

This month, Dr. Hanna’s team in Israel, as well as groups in Britain, the United States and China, all released reports on these experiments. The studies, while not yet published in scientific journals, have attracted keen interest from other scientists, who have been hoping for years that such advances could finally shed light on some of the mysteries of early human development.

Ethicists have long cautioned that the advent of embryo models would further complicate the already complicated regulation of this research. But the scientists behind the new work were quick to stress that they had not created real embryos and that their clusters of stem cells could never give rise to a human being.

“Our aims are never for the purpose of human reproduction,” said Tianqing Li, a developmental biologist at Kunming University of Science and Technology in China, who led one of the new studies.

Instead, Dr. Li and his fellow scientists hope that embryo models will lead to new treatments for infertility and even diseases such as cancer.

“We do it to save lives, not create it,” said Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, a developmental biologist at the University of Cambridge and the California Institute of Technology, who led another effort.

For decades, the only human embryos that developmental biologists could study were specimens collected from miscarriages or abortions. As a result, scientists were left with profound questions about the start of human development. Thirty percent of pregnancies fail in the first week, and another 30 percent fail during implantation. Researchers have been at a loss to explain why a majority of embryos don’t survive.

After the development of in vitro fertilization in the 1970s, scientists began studying embryos donated from fertility clinics. Some countries banned the research, while others allowed it to proceed, typically with a 14-day limit. By then, the human embryo starts taking on some of its key features. A structure called the primitive streak, for example, organizes the head-to-foot arrangement that the body will take.

For years, the 14-day rule was a moot point because no one could keep embryos alive more than a few days after fertilization. Things became more complicated in 2016, when Dr. Zernicka-Goetz’s group and another team managed to keep embryos alive close to the 14-day mark. The embryos did not survive longer because the scientists destroyed them.

Zimmer is a columnist with NYT©2023

The New York Times