CHENNAI: The subjugated land could not be more thorough in its vengeance against the colonisers. The British Raj’ biggest enemy in Madras was the heat.

Though the British were invincible in colonial India, they were completely unprepared for the tropical heat and humidity, and could not control sweating indoors.

An English surgeon in 1774, who wrote about his horrible experience of a sultry day, lamented, “Not a breath of air was there for many hours. Both man and beast, and the very fowls of the air, so sensibly felt it that some of each species fell down dead.”

If the days were bad, the nights worse. Sleepless nights were the land’s revenge.

At the end of a tiring day, there was nothing to look forward to. It was a dull, leaden night, a monotonous succession of sweat-soaked bed-sheets and sleep had become one long bad dream. Sleeping under the stars outside offered some succour, but the threat of cobras and mosquitoes loomed. By dawn, most would have simmered down to a mood of melancholic resignation. It sapped the Europeans’ health.

Most of them landed in Madras thrilled at the prospect of year-long sunshine. Back home, the fog, sleet and snow had made life rather gloomy and miserable.

But soon after landing here, the warmth of feeling the sun on their face would be replaced by the humidity and sweat.

Things got so bad that the unbearable heat affected business affairs, which threatened to derail the entire company. The Indian sub-continent’s climate was construed as severe enough to require artificial remedy.

They discovered a respite from the heat they had been longing for with the Asians – the punkah.

Discovered by the Iranians, the punkah, whose name was derived from the hand-held fan, stemmed from original inventions in the far east, where it was hot, and slavery was common. From the Mughal influences, the company picked it up, and the punkah became a standard feature of European homes, offices and barracks in colonial India. Soon it was used elsewhere in the British Empire and in slave-serviced homes of early America.

The punkah was a wooden framework, mostly with cloth extensions, hung from a hook on the ceiling with an attachment of rope/wire, which was pulled at the other end by a human operator. The to-and-fro swinging of the device created a gentle breeze, which fulfilled the objectives of ventilation and cooling. Its’ use was a seasonal affair spanning 6-9 months depending on the experience of the ‘hot weather’ across different locations in the Indian sub-continent.

One important duty of the servant was to keep his master cool. The European households were already overstaffed. One early memsahib writer wondered why the cat alone in the house had no servants while everything else had been taken care of by a dedicated native.

In many houses, the servants outnumbered the bosses by 20 to one. A few more servants to cool them didn’t really matter.

Initially, the heat went into their heads and with comical absurdity, they threw privacy concerns and didn’t mind the presence of a native in the bedroom. Then, someone discovered the breeze could be generated even if the coolie sat in the verandah, and pulled the punkah through a hole in the wall.

This allowed servants, called punkahwallahs, to sit in an adjacent room. The British officers also preferred punkahwallahs who were auditorily-challenged so that they could speak freely about anything without being overheard.

Soon, someone fitted a pulley in the hole and made it even simpler. But not for long. Friction arose and the pulley would begin to creak. The rhythmic squeaks were as bad as the humidity and ruined the Englishman’s sleep. The chief engineer of the Madras Railway Company and bridge builder, Edward Waller Stoney, invented and patented the Stony-silent punkah wheel. Stoney never did attain worldwide fame. His grandson, however, did.

Inventiveness does run in the family and Stoney’s grandson, Alan Turing, the father of computer science and artificial intelligence, broke the Nazi code and is credited to have saved the world from Hitler’s tyranny.

The personal service of punkah pullers became necessary for 24 hours a day as health concerns became a perennial problem in the urban European households and army barracks in the mid-19th Century. Noticeable transformations in output and health were noticed, and the colonial state had to bear the costs.

Consequently, there emerged a separate group of servants — punkahwallahs/punkah coolies — entirely dedicated to this task. Large groups of primarily male servants filled up these seasonally available positions in regions of British India. Soon, definite time-bound shifts covering portions of the night and day emerged. Most British homes had punkahs in every room, even in the bedroom, dining and even bathing rooms. The servant would call out to the punkah coolie and tell him which room to operate.

The punkah became an essential attribute of European life in colonised India. By the 1840s, it was being described as an ‘indispensable’ fixture in ‘all principal apartments’ of a European home.

There was also racial discrimination in the offices where natives were not allowed punkah pullers as they did not use it at home and were more used to the climate. But the emerging middle and upper classes of natives mainly, Indian dubashes and merchants, had their houses fitted with punkahs as well.

Migratory non-landed agricultural labour population offered a considerable supply in colonial India to be mobilised for temporary works. Huge populations migrated from the village to create these breezes. Punkahwallahs or punkah coolies, were hired temporarily every hot season, and separate from the existing retinue of household retainers or barrack menials. Soon, other staff found it derogatory to pull the punkah.

This enterprise of punkah-pulling was delegated to the ‘lower’ ranks of servants employed in wealthier European households, often the palanquin-bearers. Palanquin and the punkah were complementary. One didn’t go out in the night and one didn’t need a punkah when travelling in a palanquin.

Dexterously plucking at the rope in rhythmic intervals wasn’t a hard job and many mastered it by using their toe do the work when they lay on the floor. But it was not always easy to stay awake when the men in the next room snored in comfort. Many wobbled in their sleep and often let go of the rope or lay down and slept in the roughly disrupted circadian rhythms or simply, out of exhaustion.

A sense of injury in a sleepy man was an emotion too complex to analyse. The Englishman who wakes up drenched with perspiration, and sees a snoring coolie who should have been fanning him to sleep, would not have a sense of humour about it. Many violent quarrels sprang up between the awakened client and the sleepy puller.

Across India, punkah coolies were suffering from fatal acts of violence by the Europeans but the courts were not sympathetic to the natives. These cases also yielded the minimal conviction of ‘simple hurt’, with ‘culpable homicide’ being ruled out.

Though fatalities were not recorded in Madras, there was an interesting litigation. In April 1873, a coachman Permall in Madras went to court that his employer Captain Graham dismissed him with back wages pending for refusing to pull the punkah. The judge dismissed the suit, of course, terming it ‘wilful disobedience’.

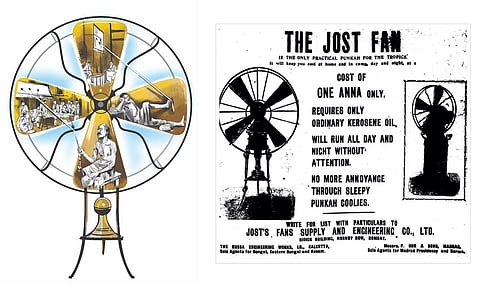

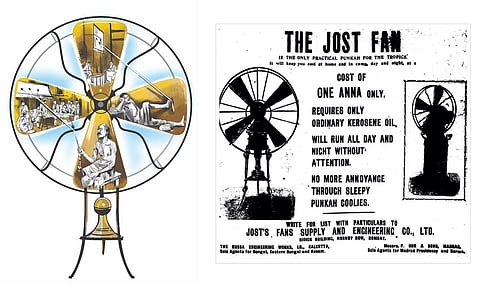

Technical alternatives to manual punkah pulling was the steam-driven improvement in princely state Awadh, as early as 1819 but it was not popular in Madras. Eventually, the punkahs were replaced by the kerosene-run rotating fan and the punkah and its pullers disappeared. The initial advertisements of the fan run on kerosene oil notably mentioned ‘no more sleepy coolies’.

It was not until the 1880s that fans went electric. Inventor Philip Diehl installed an electric motor he had designed for the Singer sewing machines into a ceiling fan. But for long, Indians continued calling the ceiling fan as punkah in their colloquial usage. In historic retrospection, next to the cannon, it was perhaps the punkah that built the empire for the British.

Unhindered by the heat, the company proceeded to divide its attention between textiles and land-grabbing. In fact, the punkah stopped the Englishmen from exiting India long before, and on their own, without the efforts and prodding from Gandhi and his folks.