National Family Health Survey: Convoluted, Outdated, Irrelevant

Before 1990, the data from sample surveys conducted in India by the government or other agencies were considered confidential.

CHENNAI: Commissioned in 2023 at estimated cost of around Rs 200 crore, the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) is currently under way. But, instead of an all-purpose, nationwide survey, which is often riddled with inaccuracies, poorly-framed questionnaires and the sample based on old census, it’s time to conduct for State-specific surveys, with clear and well defined objectives on issues relevant to the respective states, writes Padmavathi Srinivasan

Before 1990, the data from sample surveys conducted in India by the government or other agencies were considered confidential. The original data set was not allowed to leave the country and only the published results were allowed to be used outside.

This was characteristic of communist and socialist governments, wherein the state exercised total control over national data. This is still the case in China today.

India, on the other hand, has moved away from data access and usage restrictions since the 1990s with the advent of economic liberalisation. Not only did foreign governments, international NGOs and foundations become partners in survey-taking in the country, but the data and findings were also shared with several foreign institutions and scholars.

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS) was a part of the economic liberalisation and globalisation of the Indian economy and the first of its kind to be ever undertaken in India at that time. The survey was a part of the larger Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) programme initiated and funded by the USAID in 1984 conducted in over 90 developing countries. The name of the DHS survey in India was changed to NFHS to provide greater emphasis to family and health issues.

Origin

The first round of the nation-wide NFHS was started in 1991 by the Government of India and was referred to as simply ‘NFHS.’ It was initiated to provide reliable estimates on fertility and family planning, unmet needs of family planning, desired family size, child immunisations and malnutrition, pregnancy outcomes, and maternal and infant mortality and their causes.

The sample was 88,562 households and 89,777 women in the reproductive ages of 13-49 years, and data was collected in 3 phases from April 1992 to September 1993.

In undertaking the NFHS, it was also hoped that the survey capabilities of the 18 Population Research Centres (PRCs), under the control of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) and located in different states, could be strengthened with the training of the staff as field-data collection agencies, and later, as partners in analysis and report writing, so that these centres could continue to undertake similar surveys after the NFHS operations were completed.

Even in NFHS-1, the questionnaire was considered fairly large with around 46 pages of approximately 608 questions (of course, with many skip questions and comments by the interviewer) mostly on fertility and family planning. For the first time, samples of blood were taken from the respondents and checked for HIV antigens. Data on the prevalence of HIV, which was a critical health issue around the world at that time, was provided from the survey.

The survey was a major landmark in the development of the demographic database for India and the data were fairly reliable when checked with other estimates. The success of the NFHS was hailed and the data welcomed by the academia and policy makers. The findings were published in a 1993-94 report giving data on fertility trends and differentials, acceptance and use of family planning methods, and other parameters.

However, as they say, success can sometimes go to one’s head and make the person to do foolish things. In a way, this is true of the NFHS.

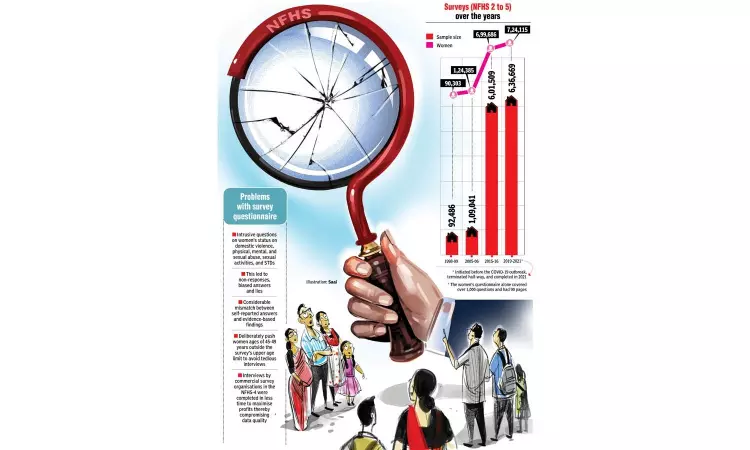

The survey was repeated over the years. The NFHS-2 was conducted in 1998-99 with a household sample size of 92,486 and 90,303 women in the reproductive ages 15-49 years. The NFHS-3 conducted in 2005-06 covered 1,09,041 households and 1,24,385 women. The NFHS-4 in 2015-16 covered 6,01,509 households (nearly 7 times the household sample size covered in the NFHS-1) and 6,99,686 women. The NFHS-5, which was initiated in 2019, had to be terminated half-way due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and completed in 2021. It covered 6,36,669 households and 7,24,115 women.

By NFHS-5, the women’s questionnaire alone covered over 1,000 questions, running to about 90 pages. Additionally, all rounds of the NFHS had separate village-level and household-level questionnaires, and from the NFHS-2, a men’s questionnaire was added.

Anthropometric tests and blood test biomarkers were also carried out on select women and children in few states in all the rounds. It was a heavy workload.

Sensitive questions

However, not only did the sample size and number of modules increase in every round, the questions in the survey became boldly intrusive.

While the first NFHS had questions to mostly fertility and family planning, the NFHS-2 saw the inclusion of a few questions on women’s status and domestic violence.

From NFHS-3 onwards, questions on physical, mental, and sexual abuse, sexual activities, and sexually transmitted diseases became predominant. Based on the NFHS-3 findings, a special report on ‘Gender equality and women’s empowerment in India’ was released, which was followed by a barrage of academic publications, reports, and news articles on social and economic status of women in the country.

In fielding sensitive questions, we must expect high levels of non-responses, biased responses, and untruthfulness. In their article, ‘Sensitive questions in survey’, published in the Psychological Bulletin in 2007, R Tourangeau and T Yan noted considerable mismatch (as high as 30-70%) between self-reported answers and evidence from measurable methods on sensitive topics such as drug use, having illicit drugs, and abortion.

Untruthful responses may stem from not wanting to give the perception of going against the social norm (social desirability) or because of the fear that the information may be leaked to the public or authorities. It is therefore presumptuous to expect women respondents in India to truthful reply in the affirmative to questions, such as ‘Have you had a disease which you got through sexual contact?’, ‘How many sexual partners, other than your husband, have you had?’ and ‘As a child or as an adult, has anyone other than (your/any) husband physically forced you to have sexual intercourse or perform any other sexual acts when you did not want to?’ and whether the abuser is ‘current/former husband; father/stepfather; brother/step-brother; teacher, priest/religious leader; police; friend/acquaintance’.

Such sensitive questions can be asked by doctors or health professionals in a hospital or treatment setting, or law enforcement agencies (in assault cases) than casually by strangers in a national survey. Such questions will not be asked in general demography and health surveys in the West, especially when the questions are not aligned with the survey purpose and objectives.

Unfortunately, it has become common for Western social scientists and feminists to exploit the uneducated, and naïve populations in developing countries to field such questions in a demographic survey and use the outcomes to label societies as ‘misogynist’, patriarchal’, ‘underdeveloped’, or ‘traditional’ (in the western sense to imply with not modern or progressive). As the DHS programme is fully or partly funded by the USAID and large international foundations, the governments in developing countries allow the indiscriminate addition of sensitive questions.

Quality of data

Many Indian demographers have expressed concerns over the declining quality of the NFHS. In ‘Quality of Data in NFHS-4 Compared to Earlier Rounds: An Assessment’, published in the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW) in 2020, K Srinivasan (who initiated the first NFHS survey in 1992-93) and R Mishra note that the data on reported age of death of a household member, sex ratio in the different age groups, and nutritional and immunisation status of children in the NFHS-4 are likely to be inaccurate compared to earlier rounds.

Based on the analysis of sex ratios in the NFHS-4 data, the authors surmised that interviewers may have deliberately pushed the women’s ages of 45-49 years outside the survey’s upper age limit (49 years) to avoid tedious interviews. Excessively long questionnaires are known to cause mental and physical fatigue in both interviewers and respondents.

Further, authors note that the average interview time in the NFHS-4 for women without children was 49 minutes compared to 65 minutes for women with at least one child. Moreover, interviews by commercial survey organisations in the NFHS-4 were completed in less time than those by the PRCs, probably because private organisations rush through the job to maximise profits, thereby compromising the quality of data.

There is difficulty in generalising non-demographic data to the wider population because of the way the NFHS is designed. The NFHS was designed to primarily study fertility trends and family planning practices, pregnancy care and outcomes, maternal and child morbidity and mortality, and their related causes, and child nutritional and immunisation status. The sampling design and sample size for the NFHS was stratified, multi-stage, and followed systematic sampling.

Until NFHS-4, representative samples were selected at the State level to provide reliable estimates of fertility. For crude birth rates, it was collected at the State level and from NFHS-4, at the district level. The sample size was selected on the basis of achieving a given level coefficient of variation or sampling error (5%) in the estimates of fertility and crude birth rates. The survey was, therefore, not designed to study topics such as domestic violence, women’s status, and alcoholism.

Unfortunately, it has become the practice to add questions to the NFHS on whatever issue is in fashion at the time. Because the original survey was designed according to the sampling design principles, the error of design effect needs to be considered when questions on other topics are added.

The design effects on the errors of many variables added later may be considerably higher than what has been estimated.

For example, levels of estimation of domestic violence or sexual assault in the general population can be expected to be lower when the sample is based on random sampling and higher when qualitative methods are used, on say, women’s groups. Moreover, the sampling weights for cities, towns, and villages in the NFHS are based on the census nomenclatures.

In the last 10 years, India has experienced rapid urbanisation, especially in states like Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, where it is difficult now, to find villages that were identified in the 2011-Census in existence. Many have either transformed into towns or become a part of the nearest city.

However, the household sample-weights for rural and urban areas used in the 2015-16 and 2019-21 NFHSs are still based on the 2011-census, leading to inaccurate conclusions.

Some other concerns on the NFHS were expressed by demographers Irudaya R Sebastian and KS James in the ‘Third national family health survey in India: Issues, problems and prospects’ published in the EPW in 2008.

Selection of survey agencies

Perhaps a controversial point is the practice of selecting agencies based on the lowest financial bid rather than on who is the most capable and experienced. This may have, according to K Srinivasan and R Mishra, contributed to the declining quality of the NFHS.

No one would have imagined when the NFHS first started that the survey would become a major commercial enterprise, with private organisations competing against each other to secure contracts.

In NFHS-1, the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, was designated as the nodal agency by the Union ministry for providing coordination and technical guidance, and the PRCs were responsible for data collection in different states. But, while the IIPS continued to be the nodal agency in the other rounds, many PRCs were replaced by commercial agencies, whose organisational goals differ considerably from those of non-commercial research organisations.

Way forward

Despite emerging concerns over the quality of NFHS data and recent recommendations by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) in New Delhi, the sixth round of the NFHS was commissioned in 2023 at the cost of around Rs 200 crore, and is currently underway.

Given the increasing complexities and confusion in the NFHS purpose and objectives and escalating costs in undertaking the project, it is advisable to retire the NFHS programme in the country. Since the states are at different stages in the demographic, economic, and social development, it makes sense to have State-specific surveys, with clear and well defined objectives on issues relevant to the state, instead of all-purpose, nationwide surveys.

Instead of relying on commercial enterprises for data collection, the PRCs, which have several decades of skill, knowledge and expertise in undertaking demographic and health surveys, should be utilised in the State-specific surveys. It’s known that all good things (eventually) come to an end, but knowing when to quit ahead requires wisdom.

—The writer is an independent research consultant in demography